3.0 Models for understanding customers

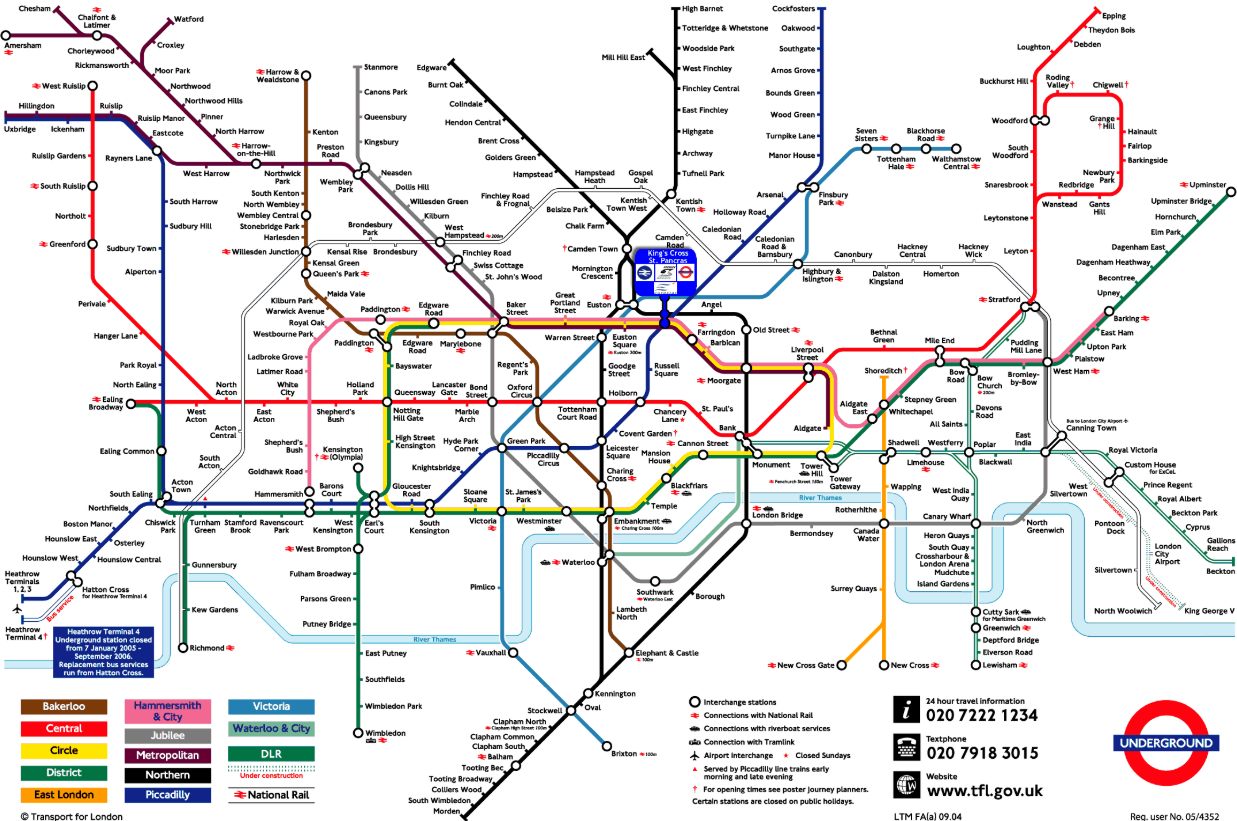

In 1931, Harry Beck changed London. If you haven’t heard of Harry Beck that’s not necessarily surprising – he neither sought nor received fame in his lifetime. He was neither an architect, a politician, an engineer nor a titan of industry but you’ll recognise his work. You’ll also recognise its impact far further afield than just London – in Amsterdam and Sydney to name but a few places.

London is a very old city. Foundations of a large timber structure, dated to between 4800–4500 BC were discovered on the south bank of the Thames in 2010, but the city we recognise today as London is most commonly agreed to have been founded by the Romans in 47AD. Reinvented through wars, disease, fire and technology, London has continuous changed with the times, and with the onset of the industrial revolution its population soared. Between roughly the 1830s and the 1920s London was the world’s largest city, the challenges of which forced new innovations and changes. As traffic congestion due to the influx of population grew, London became the first city in the world to build a local urban rail network. Through the 1800s into the early 20th century London’s transport system grew rapidly as private companies built a new and exciting network of railways above and below ground to connect people to destinations more quickly and more directly than ever before.

To help travellers use their networks, each private rail organisation each issued maps showing stations, routes and destinations of their transport options, but with different companies running separate lines the system was a mess. Companies didn’t want to show lines run by their competitors leading to a complete lack of coordination in the design, layout and placement of information. Commuters had to consult multiple maps to plan their routes and the lack of a clear plan made the whole network harder to access. If you think Google Maps is a pain because it considers road OR rail OR bike rather than a say, bike to the station, catch the train, then catch a cab, then imaging how frustrating and unhelpful the system would be if it only recommended some roads or rail lines and failed to even acknowledge the rest.

Recognising this problem, attempts were made to create unified maps showing all of the lines in one standardised view. Unfortunately, London’s millennia of evolution and the geography of the River Thames made these maps difficult to use effectively. The ancient City of London had a concentration of stations and platforms that became crushed, crowed and hard to discern from each other on the map while the further out areas had to be cut off to make the scale of the map legible. For those unfamiliar with London, the City is a central city within the city, centred on the ancient centre. Stations for separate lines near to each other were hard to distinguish from stations supporting multiple lines. And the underlying street map made the whole thing harder to read. Enter Harry Beck.

Born in 1902 Beck was a technical draughtsman who worked at the London Metro Signal Office. Beck was never commissioned to develop a map for the London Underground (though some reports suggest he was paid a fee of five to ten guineas) but after being fired by the London Metro Signal Office Beck set to draughting a more user friendly design. Beck realised that when people were travelling underground, the landscape and geographical accuracy of the map didn’t mean all that much. They arrived at a station, got on a train, travelled underground, got off at another station and emerged at their destination. It didn’t matter where you were going relative to every street around you. It mattered where you were going relative to your underground line. And so that’s what we drew. Using regular lines, shapes and angles, Beck stripped away the complexity and drew up a visual model of the London Underground network. I bet you don’t need to think hard at all to visualise it in your mind. You might not know the details of which station is next to which other, but its iconic simplicity is a landmark of design. In 1932 a pilot of 500 maps was produced and it was put into full publication in 1933 with a print run of 700,000. Feedback was so positive that a large reprint had to be ordered only a month later.

Harry Beck never received the recognition he deserved in his lifetime. Posthumous recognition is a rarely satisfying to the departed. But his work is regarded today as a milestone of communication. Beck took a complex, organic map and created a model of the underground network that represents the key information commuters needed to know. Where am I? Where am I going? What lines connect the two? Its purpose is to visualise information and simplify it to make it useful. You cannot walk around London using a Tube map, its purpose is only for public transit links. Complexity is easy; useful simplicity is difficult.

If you go to buy a house you might speak to a realtor or estate agent, you might visit multiple houses before you make an offer, which you may have to negotiate a few times. Once you have an offer accepted you need to engage a solicitor, then you gather more details and you get a survey, which may uncover issues or costs that you haven’t foreseen. Until you finally agree an exchange date, the deal may not go through and you then start the process again. And until you finally move in you’re still in the process. It may be similar but different for other expensive items – cars, private schooling for children and holidays. By contrast, filling up an office stationary cabinet that’s running low could be very straightforward. ‘Consumer’ does not automatically equal simple and ‘business’ does not automatically equal complicated. When we talk in a business context about long sales cycles, multiple stakeholders and high cost or right, what we’re really talking about is complex sales. As business solutions have become more integrated, buying groups have become larger, business impact has become bigger and communication and alignment through the buying process has become more important, meaning deals take longer and agreement is harder to reach – or more concisely, sales have become more complex. There are other characteristics of complex sales. More research is done without engaging with a sales person. Priorities and requirements are agreed before suppliers are brought into the conversation. Decisions are made, reversed, refined and re-evaluated constantly throughout any complex sale and the more strategic the purchase, the more complex the customer engagement is.

What does this have to do with Harry Beck? Well, recognising this the thinking goes that the customer journey model has also become more complex and that marketers need a new model to visualise and understand it. As result there are customer journey models that are infinite loops, circles, wheels, hourglasses and cylinders and, much the same way that the objective of the sales funnel is misunderstood so too is the purpose of a customer journey framework. Buyer journeys are non-linear. They never have been. The idea that because purchases are now more complex – which we shouldn’t doubt – necessitates a more complex model is to misunderstand the customer journey model’s purpose.

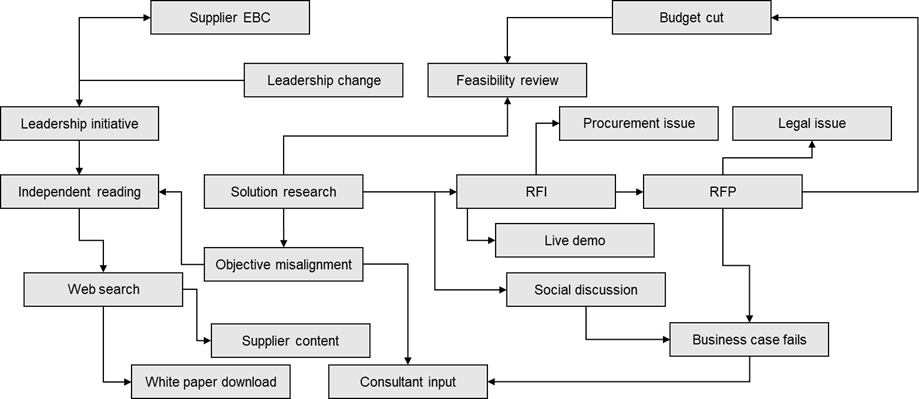

The visual below is one example of the activities a customer may go through to complete a purchase. This organisation could well be unique in being the only organisation that has ever gone through these steps in this order. Its complex, its messy, and there are infinite variations. Maybe the business case fails earlier on for someone else or procurement are only involved later. Maybe it flies through and gets signed off with ease or maybe its delayed for months due to a leadership change. The steps every organisation goes through on its journey to purchase are unique. So if Marketing is an engine for Sales that functions by scaling for efficiency, how can an a journey like this be operationalised for scale?

The answer is, of course, that a customer journey like this cannot be scaled. Much like Harry Beck’s Tube Map, customer journey frameworks are models of reality. They’re maps of how customers can get from A to B that remove the extraneous information that makes them impractical to implement and use. The London public transport network didn’t reimagine the Tube map when the Elizabeth Line was added to it, much the same way as the customer journey doesn’t need to be redesigned because there is an increased preference towards self-research before Sales are engaged. The customer journey framework is a model of the customer’s purchase path, not your marketing activity. Customers still go through the same steps; they just spend more or less time in each as preferences, technologies and legislation evolves.