5.2 How do we plan?

Jerry Brown, the 34th and 39th Governor of the US state of California was once quoted as saying “The reason that everybody likes planning is that nobody has to do anything.”

Conceptually, we all get what a plan should do. ‘Today, I need to go to the shops, visit my friend and grab some food for this evening on the way home from work. Traffic is usually busy at that time so I’ll start work early to I can leave a little earlier, visit my friend first, so food isn’t sitting in the car while we meet, and swing past the shops that are next to the supermarket to save some driving. I’ll try to be home for 7.30, so I’ll let my partner know I’ll be a bit later than usual.’ Plan sorted. We have a goal, we have an order, we understand the compromise (starting work early) and we know who else needs to be informed. So why does so much marketing planning feel like its over-complicated?

Planning for yourself is, of course, very different from integrated planning in a complex enterprise marketing organisation. There are more people that need to be consulted, which leads to more opinions that can impact the plan. More opinions mean more data is required to reconcile them and more discussion is necessary to understand the impact of any decisions. On top of this, the stakes are higher, so risk aversion is also consequently greater. By the way – these are also the same challenges sales teams come up against when trying to get a prospect to progress through a purchase process: lots of opinions, high stakes and a desire to do it right. So given the complexities of doing it well and the importance of doing it right, there should be a clear model for the whole organisation to follow.

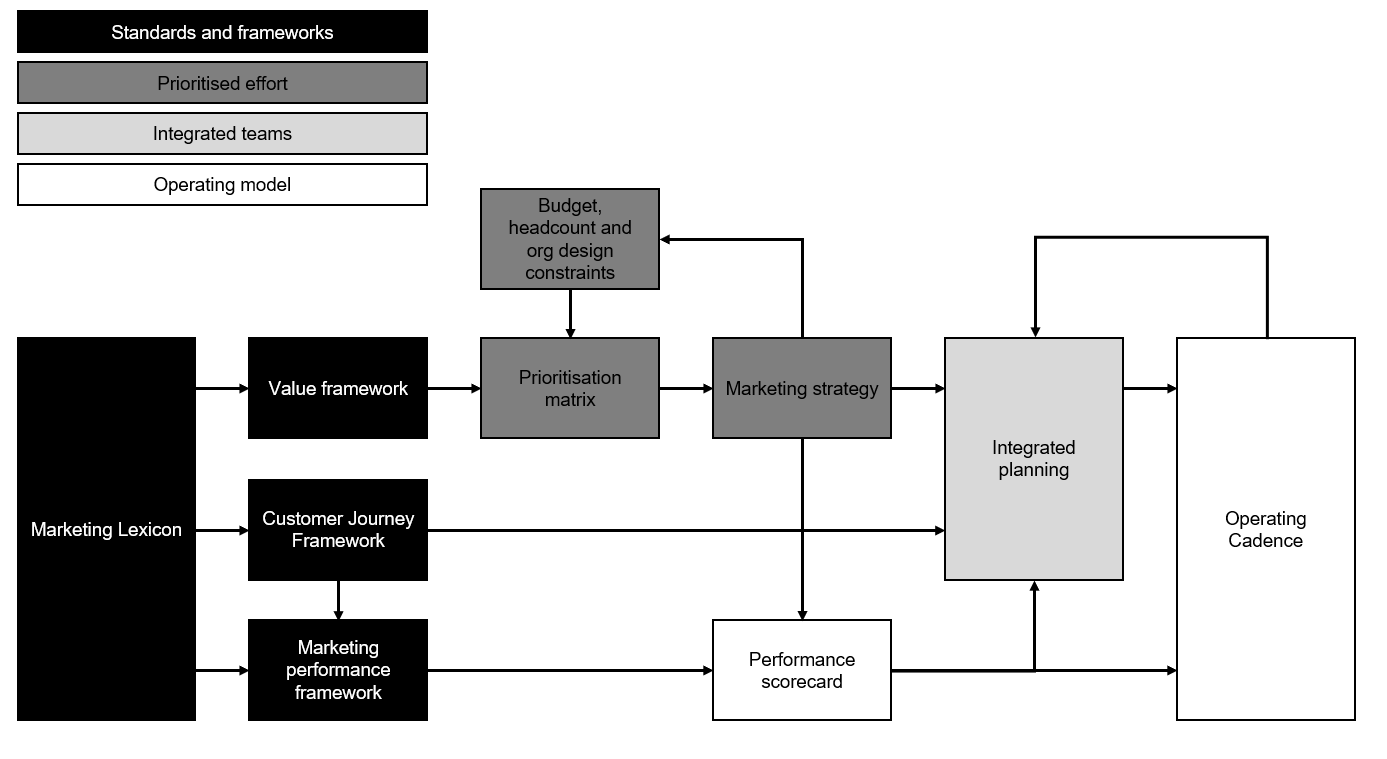

The purpose of planning is to get alignment on how to execute your strategy. To align on how you will deliver work to meet your goals and objectives. Integrated planning is the process of driving that alignment as one marketing organisation.

Planning in a silo with your own budget, your own resource, your own team, your own channels, your own agencies and only your own goals is easy. It’s the equivalent of working out your drive home via the shops. Within an enterprise marketing organisation, though, it creates inefficiency and disfunction. Those very constraints of looking only at the budgets, resource and channels that each team owns means that what customers see is those same organisational divides made real in your marketing. Opportunities to force multiply, to learn from more data and to bring functions together are entirely missed without integrated planning. ‘Easy’, does not always mean ‘best’ when it comes to planning.

But ‘best’ does not have to equal ‘hard’ either. Planning needs to be done to the right level. Working out how many workshops you’ll run in a quarter may be too far into the weeds for an annual marketing plan being led by an SVP. But it may be right for the senior manager who has to plan their personal goals. Importantly, though, an SVPs plan has to connect to the Senior Manager’s plan if they are in the same organisation. The altitude at which planning is completed is important. This is the purpose of integrated planning – to make sure relevant information roles upwards, downwards and sideways in an organisation so that teams work together, rather than in parallel with each other.

Overplanning – or at least overplanning at the wrong altitude – is a trap for many teams. Though people love to profess their love for strategy, true strategy is difficult. Strategy is the weighing up of all the potential things you could do and getting agreement on what you will do. But when strategy and planning are done right they’re powerful allies. They layer upon each other. Strategic cross-functional planning reduces the need for inefficient, wasteful meetings because teams and leaders are properly aligned. The very act of planning together and aligning priorities together reduces the need for more tactical meetings because goals and approaches understand how they’re meant to work together to achieve shared goals.

When activating integrated planning, it is worth remembering these four principles:

Good strategies decide ‘Ors’. Bad strategies say’ And’. Strategy is about aligning your priorities. Planning needs to articulate those priorities in action. There are many things you could do to drive business value, but most of them you shouldn’t. Marketing strategy needs to define the things you will focus on, the things you won’t focus on and why. ‘Why’ is critical. ‘Why’ is where you need to ensure decision interlock with other functions, stakeholders and teams.

Planning is commitment. Building a plan that you, your teams or other teams fail to commit to is pointless. Integrated planning is about making joint commitments to each other. That is not to say that those commitments can’t change, but changes need to also be made in an integrated way with cross-functional agreement and communication.

It is a bad plan that cannot change. Expect that things will change. Plan that they will change. Plan your planning so that you have a process for changing the plan. Annual plans that have detail worked out to the n’th level but forget that people may leave, budgets may be taken away, the market may take a new direction or any other impactor may occur are unnecessary effort. Plan only to the level of detail for your function that you are clear on what your priorities are relative to the strategy and other teams’ priorities, and how you with deliver them. That’s it. The integration should allow others to handshake with you and build corresponding detail.

Planning is not a democracy. More precisely, planning is hierarchical. Brand dictates look and feel, and likely values. Product Marketing dictates product or solution messaging. Thought leadership dictates content and campaign messaging. The planning process needs to understand who needs to be involved in cross functional decisions and the logical order that they flow in. Giant shifts in strategy should be infrequent so the hierarchy of planning (which does not have to represent the hierarchy of marketing leaders – it is more a functional hierarchy than an organisational hierarchy) will rarely have to undergo seismic shifts. Instead, as priorities shift so teams must consequentially respond by updating their plans.

Define the planning cadence

The traditional view of a planning process visualises a broadly linear process. Start here, do stuff here, end here. Work in, plan out. But true, great planning doesn’t look like this. Its iterative. Its adaptive. Its additive. No plan survives contact with the enemy, so the expressions goes. The point is that very few plans cover every single scenario or permutation and even if they did, it doesn’t guarantee something else doesn’t come up.

Perhaps the case study for overplanning is the Apollo manned flight programme. Engineers planned, tested, replanned, retested, re-replanned and then re-retested every scenario they could think of to ensure the success of the Apollo missions. They had astronauts simulate ever computer error code they could think of, every situation that could occur until they felt they had a plan in place that could cover it. If this happens then do that. They tried to take all chance out of the equation. And it was just as well they did – lives were at stake. And were it not for a test run mere days before the Apollo 11 flight – resulting in an error that actually went on to occur on the Apollo 11 mission – they wouldn’t have known how to deal with the situation and would most likely have had to abort. But on Apollo 13, an accident they hadn’t planned for occurred and they still had to adapt. If you’re saving lives, putting people in danger or running exceptional risks, highly detailed planning years ahead of time is a good idea. If you’re planning a marketing campaign, getting incremental data and making risk-informed decisions will probably produce better plans.

In his book Atomic Habits, author James Clear talks about four laws of building good habits: First, make it obvious – be able to recognise when you need to do something. Second, make it attractive – make it positive to do a thing that you want to do. Third, make it easy – don’t try to eat the meal in one go, start with some light bites. And fourth, make it satisfying – reward yourself when you’ve done it. The habits of the most effective individuals are also the same as the most effective organisations and highest performing teams: they have a rhythm of business to recognise when they need to do something, they catch it early enough to avoid it becoming a major problem, they make it clear how to action and they reward for high performance. This is also the nature of data-driven planning.

A rhythm of business – also known as an operating cadence – is the flow of reviewing data, identifying opportunity, delivering work and evaluating success that an organisations runs to. Sometimes this may be established by leadership, sometimes by reporting or compliance requirements, sometimes by budgets. For many enterprise organisations there will be some element of quarterly or annual operation, usually driven by the need to report or review results with investors. The operating cadence may support an annual planning process, quarterly business review and monthly performance reviews, with action plans resulting from each. For example annual planning may conclude with a review and iteration of marketing strategy and major campaign plans, quarterly business reviews may result in program changes within the campaigns and monthly reviews may result in tactical updates. But for all of them there will likely be a question: continue what is already working, unblock something that may have become stuck, start something new to catch up, or reprioritise work already in progress? It is as simple as that.

In practice there are a few additional nuances. Cross-functional collaboration is essential to success. An operating cadence that doesn’t include the right people in reviews is an unproductive exercise. Similar to planning, meetings that fail to align and capture clear action commitments, the performance of which can be evaluated in future reviews, have little value. Slowly crawling towards inevitably failing to hit a target without taking the needed action is a sign of a team with severe dysfunction.

Operating cadences need to be established across all layers of the marketing team. Predictably reviewing cross-functional commitments drives accountability and progress. Most teams also prefer this type of working environment to the panicked escalation meetings where its typically too late to change course and the only resort is to point fingers or hope that it will be done better next time. The goal of an operating cadence is to establish the review frequency by which problems are solved before they impact business performance. Consistent, predictable, performant value delivery is only possible when there is a clear operating cadence.