5.4 How do we speak?

When Apollo 11 landed on the Moon in 1969 it both delivered on the mission set out by President Kennedy at the start of the decade and demonstrated that precision landings on the Moon were possible. Apollo 12 followed soon afterwards and proved that lunar missions targeted at specific landing locations were repeatably and reliable. On April 1970 Apollo 13 launched with a target landing site near Fra Mauro crater. Fra Mauro was believed to contain material ejected from an impact early in the Moon's history and the full mission objective was to “perform selenological inspection, survey, and sampling of materials in a preselected region of the Fra Mauro Formation. Deploy and activate an Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package. Develop man's capability to work in the lunar environment. Obtain photographs of candidate exploration sites.” Of course, the mission didn’t go as planned. 180,000 miles from the Earth an explosion in one of the oxygen tanks during a routine piece of maintenance put the crew’s life in eminent and immediate danger. Oft misquoted, Jim Lovell, mission commander, radioed Houston mission control with the immortal message. "Okay, Houston, we've had a problem here." When it became clear that not only would they not be able to land on the Moon but they may not be able to make it home all efforts were thrown into returning them safely. The Lunar module was repurposed as lifeboat to save power, carbon dioxide scrubbers were repurposed using plastic bags and duck tape and urine dumps were cancelled to avoid pushing the craft off course. Through force of ingenuity the crew landing safely on April 17th in the Pacific Ocean. The mission was dubbed a Successful Failure, because although the primary objectives had not been achieved Apollo 13 proved that mission control could bring the space voyagers back home again when their lives were on the line.

‘Success’ is defined by the parameters you bracket around it. Your best performing campaign is likely the one to which you attribute the most business impact for the minimum investment. But how you define ‘campaign’ will likely impact how you evaluate that success? Is a series of nurture emails a campaign? Is an event a campaign? What about emails sent to people that attended an event – is that one campaign or two? I’ve found “how do you define a campaign” to be a good question when interviewing people. It has produced some interesting results. Some people do see a campaign as a single-channel activity, whereas others understand that in an integrated marketing environment a campaign can be a more 360 degree customer experience. One answer I received described a campaigns as a ‘dialogue with customers’, which I quite liked.

Putting aside new candidates, do your teams use the same language when they refer to a campaign? Is what Google or LinkedIn refers to as a ‘campaign’ in their ad operations tools the same as a Campaigns team that builds multi-channel integrated activities would define? People’s backgrounds, experience and utilisation of different technology can have a profound impact upon their definition of campaign. And of course implementation of new technologies and standards can also be important in reshaping new experiences and naming conventions.

The Austrian-born Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein encapsulated this challenge thusly: “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” When Marketing teams use differing language to communicate with each other they align on different metrics, different objectives and different outputs, all unintentionally obscuring what all teams are trying to understand: was the effort worth it? Unfortunately, the marketer’s lot is not made easier by a general inconsistency across the industry on how to name different activities. In fact, marketers and marketing technology vendors are guilty of misappropriation and lack of alignment on the language they use, typically because they are trying to overstate a capability. ‘Account-based marketing approach’ is commonly overused as a substitute for ‘targeted approach’ with technology vendors. ‘AI’ has for years been overused as a substitute for ‘algorithm-driven’ or ‘machine learning’. Even terms like ‘brand awareness campaign’ are used to describe media activities with barely enough investment to get a few hundred clicks of engagement. Marketer’s desires to promote their successes and wins is admirable to inspire and motivate, but counter-productive when your objective is to be scientific and align on a common language.

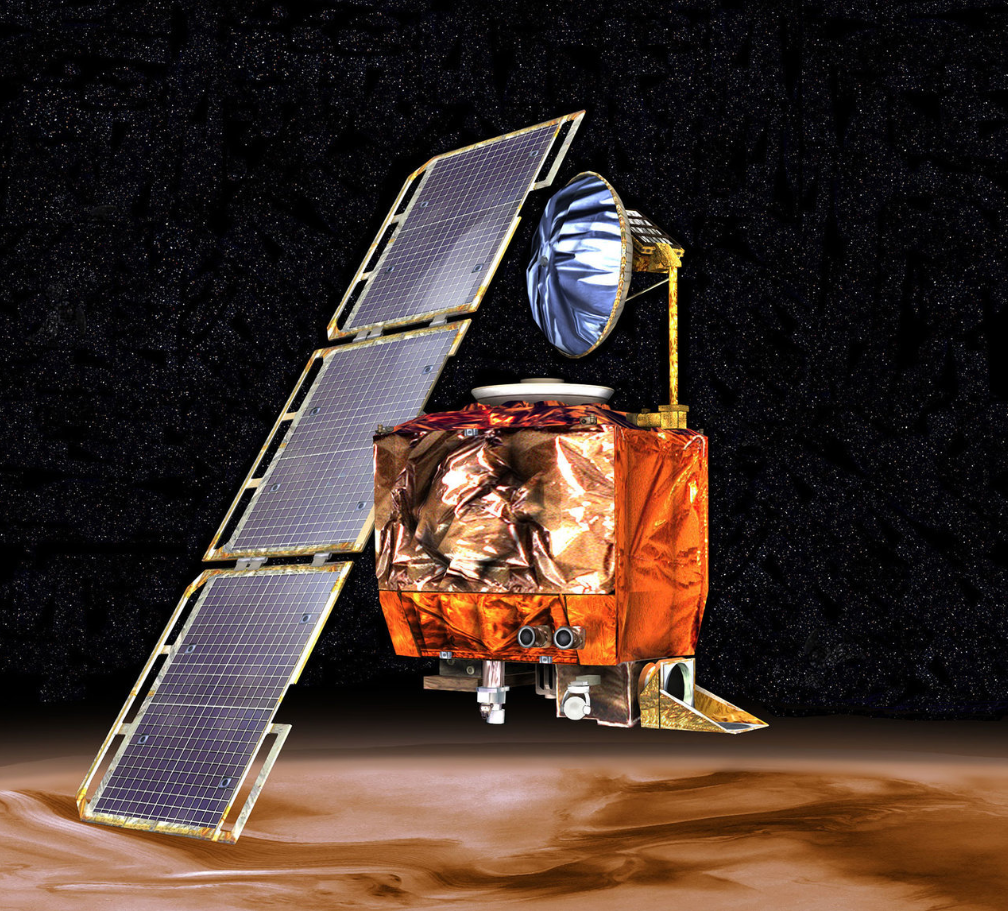

While NASA turned disaster into triumph with Apollo 13, there have been less successful examples in its history. On December 11th 1998 NASA launched the Mars Climate Orbiter. The $328 million spacecraft was designed to orbit Mars and study the climate – the name probably gave that away, though. Except the Mars Climate Orbiter didn’t make it to Mars orbit. What went wrong? Most of the calculations on orbital insertion used the international SI standard of metric units, whereas Lockheed Martin, who built the spacecraft, used the United States customary system. As a result, it either bounced off the atmosphere or crashed on the surface. Standards and definitions matter. Kilometres versus miles make a difference when you’re trying to navigate a spacecraft. If you were trying to construct the craft and one contractor understood aluminium to be thick sheet metal and another understood it to be baking foil you wouldn’t get off the ground.

Closer to home, if your Sales team uses the same deal stage to forecast a 50% likelihood of a win and 80% likelihood of a win, your ability to accurately predict revenue is going to be severely compromised. Likewise, comparing a Google Adwords ‘campaign’ to a multi-channel, integrated-theme, multi-phase demand ‘campaign’ is similarly going to cause you problems. This is why – though its hardly the most glamorous topic to write about in a book – its important when considering the How of marketing to cover the lexicon a team uses.

The purpose of a marketing lexicon is to drive a common communication framework. For NASA it was deeply embarrassing and highly costly for a spacecraft to be lost on Mars. For Marketing teams – at least the way Marketing teams work today – it simply makes you unable to make the right decisions. Lives may not be damaged or spacecraft lost, but it doesn’t mean that time, money and endless hours of effort aren’t wasted. Key to success, therefore, is getting the Marketing team to use the lexicon consistently. Leads, goals, objectives, campaigns, programs activities, awareness, discovery, consideration – a common language makes communication, analysis and collaboration easier, faster and more effective.

Unfortunately, while from an academic perspective this is easy, practically it can be challenging. As well as the activity of enabling and governing usage, one of the key limitations to perfection can be inconsistency in the way that systems describe things. Where one piece of marketing technology may describe a ‘campaign’, another technology or internal team may have a different definition. Since marketing technologies have a tendency to want to overstate their impact rather than accurately position themselves, this can make things harder. What they may call a ‘campaign’ in an effort to sound important, you may see as a single-channel activity. Unfortunately, there is little that can be done to change this, but the impact can be minimised by trying to align your lexicon to the most common uses in the tech stack.