3.3 Sources of revenue

In a world of consumer electronics where wireless Bluetooth technology is ubiquitous the idea of plugging a cable into a device may seem quaint. The earliest example of what today we would know as an audio jack was in Boston in 1877. A telephone switchboard was installed using jack switches that could be changed by plugging and unplugging various connected wires. Patents were filed in 1878, and later improved in 1880 to resemble something many would recognised today as a typical audio jack and socket. In the 1950, the mini jack was developed – known by many as the 3.5mm audio socket – and you will still find these on many laptops. Popularised by Sony in its radios, Walkmans and other equipment, the 3.5mm audio jack was the defacto standard on almost every consumer digital product with audio in or out. It was convenient, functional and ubiquitous. It worked with every device and every peripheral. It was easy for consumers; it just worked. Then, starting with the iPhone 7 in 2016, Apple stopped supporting it.

At the time this move was considered anti-consumer. It made something that every iPhone user took for granted incrementally harder. If you still wanted to connect an audio device with a 3.5mm plug on it you had to buy a proprietary adapter cable. If you didn’t have the cable, the only way of listening to music through your expensive, premium phone was to use the phone speaker. Which, lets be honest, no one wants to do for any extended period of time.

Apple’s biggest money-maker lost a key feature, that everyone used and no-one had a problem with. Apple was criticised by journalists and competitors alike, but as is often the case Apple had good reasoning behind its decision. Concurrent with launching the iPhone 7, Apple launched its first generation of Airpods wireless headphones.

Airpods, as most people know, are tiny in-ear headphones that pair via the Bluetooth wireless protocol. Airpods also supported innovative new capabilities with operating system-level software integrations, most of which only worked with other Apple devices. Thus to be able to listen to music on your premium iPhone 7, you could no longer just plug in your favourite or cheapest pair of headphones – you needed to also buy a premium set of $160 headphones.

Supporters might try to claim that the decision to remove the headphone jack was about improving audio quality, but Apple themselves have admitted to there being financial motivations. Their acquisition of Beats by Dre was a key part of the bigger picture. But more strategic than this was the move to start to lock customers into an ecosystem more tightly.

If you owned an iPhone in the past you might also own a Mac. But there wasn’t that much to connect you to needing a Mac versus just having a PC. Now, consider that if you own an iPhone you probably also need to buy a pair of Airpods. And, of course, you probably also want to back your photos us to iCloud so you have an iCloud contract. Now if you have iCloud, it integrates much more seamlessly with the rest of your Apple hardware so an iPad versus an Android tablet or a Mac versus a PC become much more attractive. This is before you even consider services like iMusic. Or other hardware like the Apple Watch. Or the other apps you buy from the iOS store that you might have to re-purchase if you moved to an alternative ecosystem.

If you move to a different phone manufacturer that cost of making a wholesale change to your digital mobility forms a worrying reminder of how much you spent in the first place to acquire this equipment. Apple is the master of upselling you on the next best thing. The iPhone may be the initial purchase, but the incremental upsold purchases are likely of equal or greater value.

If you’re an iPhone user there’s a reasonable chance that you’re also an iMessage user. Where services like WhatsApp have grown huge user bases by making their services ubiquitous across many platforms – Android, iOS, Windows and more – iMessage has remained resolutely an Apple device-only service. But for users of those Apple devices, it is essential. The little blue tick of communicating with another iMessage user makes messaging with non-Apple users more cumbersome. When you have whole families all locked into the iPhone and Apple ecosystem, things just work better and integrate better.

When Apple was investigated for potential anti-competitive behaviour it was revealed through court documents that Apple execs consciously decided not to make their iMessage service cross-platform precisely because it could undermine their lock-in and cross-sell capabilities. Apple intentionally plans how it will extend its share of wallet by upselling incremental purchases providing additive value to users; how it will lock customers into its ecosystem by interconnecting the way these devices and services work; and how it will cross-sell to other family members by making its services exclusive to its own devices. I’m not saying it’s good or right to make your products operationally inferior to lock in customers, merely noting that it is intentional.

These same principles of landing new customers, retaining those existing customers, upselling additional services to them and cross-selling to new buyers within a customer ecosystem are the basis of many enterprise sales plans. For modern marketing teams, measurements and metrics are now the guiding star of showing business value that was created. How much pipeline did I create? Which deals were influenced by this activity? What is the value of the brand?

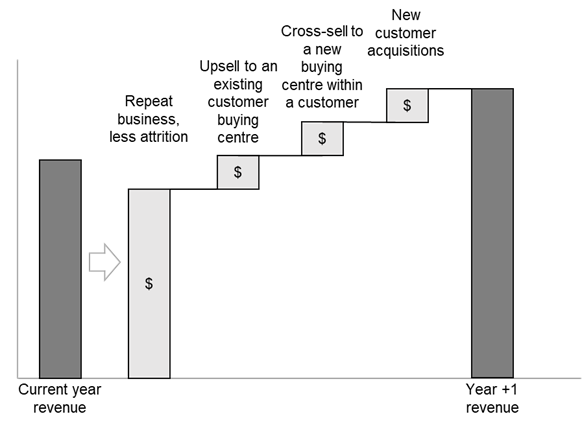

But it’s worth taking a step back to look at the big picture and consider the question: where does the revenue really come from? Though it may be over simplified for some situations, an organisation’s revenue can be said to primarily come from four sources:

Repeat business

Repeat business is a continuation of some activity that may have been initiated or sold in a previous year, where the contract value rolls over into a future year. In recent years, many organisations have looked to pivot away from capital purchases (or any form of discrete up-front purchase) towards a services model with operational expenditure. Services models, mostly enabled by the cloud, enable buyers to receive immediate benefits of their purchases without having to fork out significant capital investment up front by paying a predictable service charge. For sellers, services contracts likewise offer a level of predictable, recurring revenue, even if upfront costs may be higher.

For organisations that rely mainly upon services, repeat business will likely be the largest contributor towards revenue year-on-year. There will, however be a level of customer attrition that is built into this repeat business – customers that either through dissatisfaction, a better alternative or lack of requirement choose not to re-purchase or continue their contracts.

New customer acquisitions.

For many marketing teams, new customer acquisition is the focus. New customer acquisition results in net new investments by organisations in your devices and solutions, which goes on to feed the subsequent year’s retained, up-sold and cross-sold revenue. As a percentage of net new revenue this number may be small, as total customer value may increase over subsequent years, or may be significant in high-churn sectors. Similarly, net new revenue as a %age of total will vary according to your company retention and growth profile.

Upsell to an existing customer buying centre

Upsell strategies can depend upon the business model of the organisation, but for most enterprises after an initial purchase has been completed there will be an objective to grow share of wallet within the organisation. Upselling usually refers to getting a customer to upgrade the level of purchase they’ve already completed. For example, this may be moving from a basic SKU to a Pro option that includes greater capability or functionality. This may be achieved by first helping the customer see the value of their current purchase and building a case to expand. For the organisation upselling, this process is key as upsold products and solutions generally have higher margins, and thus directly impact organisational profitability.

Cross-sell to a new buying centre within a customer

Cross-selling occurs when a new product is purchased by an existing customer organisation. A key concept when talking about cross-selling is that of the ‘customer’. A ‘Customer’ can be confused to mean both the organisation and a team or individual, and the difference is quite significant. An individual ‘customer’ that is being sold a new solution or product will already have a level of understanding of the organisation and its capabilities. An organisational ‘customer’ may have no concept that a solution is already being used in a different part of the organisation, the value that is being delivered, or why there may be a benefit in looking at this new solution being proposed. For this reason its best to consider ‘buying centres’ within customers, rather than confuse with similar language. Buying Groups are the collective of individuals – influencers, decision makers and users among others – who are involved in purchase decisions. We’ll discuss more about buying centres in the next section. Upselling occurs within an existing buying centre; cross-selling occurs to a new buying centre. In very large enterprises where departments are not connected, it can sometimes be better to approach new cross-sell opportunities as net new engagements, and then use the existing connection at a later stage of the purchasing process as a reinforcer.

Together, Sales Operations and Marketing should work together to identify the upsell and cross-sell paths that customers go through to build value messaging and engagement journeys. For example, say and organisation has five products and lets call them Product A, Product B, Product C, Product D and Product E. It may be possible to identify that Product A contributes to 60% of new customer acquisitions and Product B contributes 30%, with the others making up the rest. From Product A new customers, customers typically buy Product C and Product D next; Product B typically buy Product E. Thus the new business plans should focus on A and B and cross-sell plans should lead towards building propositions from A to C and D, and from B to E, because these have a natural fit.

Direct source versus Partner sourced

For many business-to-business organisations, partners are a strategic component of the sales engagement framework. In this site we will not spend a significant amount of time on partners, other than to acknowledge that they are integral to many organisations. All of the fundamentals of this site can be applied to partner marketing in the same way they can to in-house sales and marketing, with the usual nuances of partner requirements.